HONE A KEEN Edge

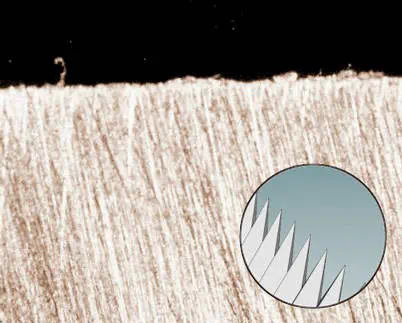

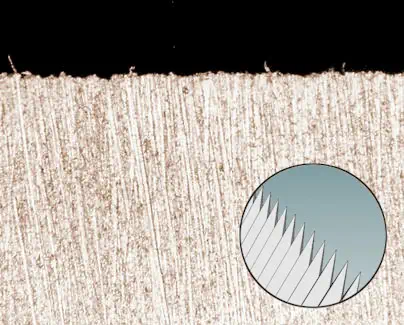

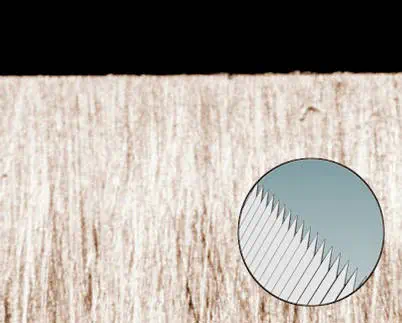

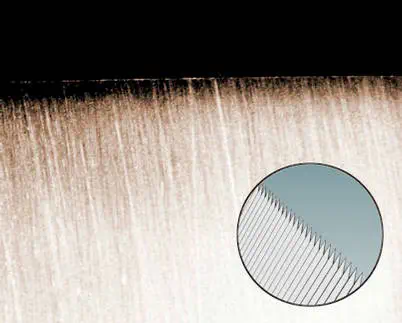

To create a crisp, keen cutting edge, finish the metal surfaces with progressively finer abrasives, making them as smooth as possible. If you use only coarse materials to sharpen, the edge will be rough. When you sharpen, the abrasives cut small grooves in the surface of the metal -- both the leading face and the trailing face. These grooves intersect at the cutting edge. On a microscopic level, they appear to form tiny teeth. The finer the grit of the abrasive, the smaller the teeth, the the closer the cutting edge comes to forming a single, crisp line -- a perfectly keen edge. Why not sharpen with just one fine grit? Because it's difficult to remove damaged areas and restore badly worn edges with fine grit. You also run the risk of overheating the tool if you use power sharpeners -- fine grits produce heat faster than coarse grits. Coarser grit removes metal faster and keeps the tool cool. It's faster and safer to work your way up through a series of progressively finer grits. How fine should you sharpen? That depends on the tool and your personal preferences. For most applications, it’s sufficient to grind and hone to between 500 and 700 (U.S.) grit. But many craftsmen polish and strop to 1,200 grit and beyond for the keenest possible edge.